Production and Estimation of Ascorbic Acid in Biocatalytic Enzyme from Citrus Fruit Peels for Bioremediation of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Fields and in-silico docking, molcular modeling and mutational analysis

- 10 minsDayananda Sagar College of Engineering, India. Summer 2021

Background

Heavy metals, which are metallic elements with a density higher than water and a non-biodegradable nature, pose a significant environmental and public health concern due to human activities such as industrialization. The persistent nature of heavy metals in the environment allows them to accumulate over time, leading to increased levels of toxic metals such as arsenic, chromium, cadmium, lead, and mercury. Of these, chromium is widely used in industries such as metallurgy, chemical, military, textiles, and machinery, resulting in its natural conversion to the more toxic form, Cr(VI). This process leads to increased accumulation of chromium in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, thereby affecting human, animal, and plant physiology. The presence of chromium in food chains can pose a serious health threat to secondary and tertiary consumers. Moreover, high levels of heavy metals such as chromium can induce oxidative damage in plants, affecting plant health and their ability to support other organisms.

To address heavy metal pollution, traditional methods include physical, chemical, and biological approaches. Among these, microbial remediation stands out as a natural process that utilizes microorganisms to break down or transform pollutants. Microbes are known to utilize toxic compounds as a source of energy for their growth and development through different metabolic pathways. This ability makes microbial remediation a cost-effective and eco-friendly approach to remediate heavy metal pollution.

Recently, there has been a surge of interest in bioremediation of heavy metals using Bioenzyme, which is a fermented product of vegetable and fruit peels, jaggery, and water. The use of Bioenzyme for bioremediation of heavy metals is an attractive proposition since it offers an eco-friendly and cost-effective solution to heavy metal pollution. Additionally, studies have shown that Bioenzyme not only removes heavy metals from the environment but also enhances the nutrient content and survival rate of crops. This low-cost technology could be a potential solution to address heavy metal pollution while simultaneously promoting sustainable agriculture practices.

The objectives of this project includes:

- Using an appropriate bioreactor, produce and biochemically characterize Bioenzyme, while also quantifying the amount of ascorbic acid produced in the process.

- Analyze soil and plant samples to determine the concentration of hexavalent chromium present.

- Conduct pot experiments to investigate the bioremediation potential of Bioenzyme.

- Construct a three-dimensional model of chromium(VI) reductase, followed by molecular docking studies with chromate and dichromate to understand their interactions.

- Employ in silico site-directed mutagenesis to identify the essential active site residues involved in the reduction of chromium(VI).

Methods

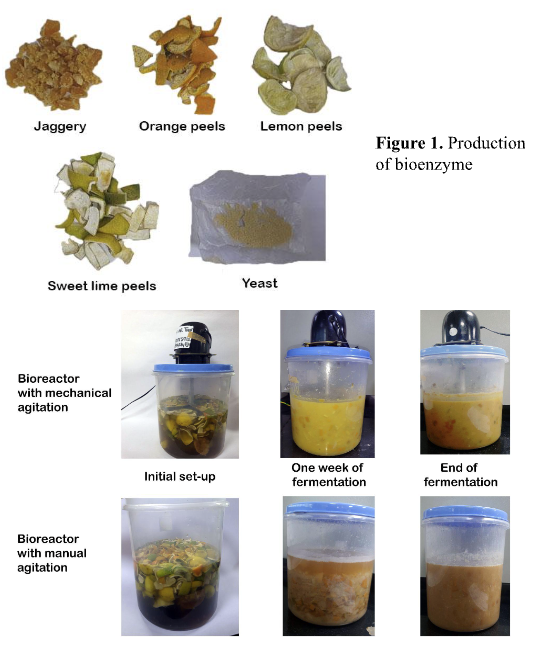

- Production of bioenzyme

Bioenzyme production requires jaggery, citrus fruit peels, baker’s yeast, and water in a specific ratio. In two batches, 0.25 kg of each citrus fruit peel and jaggery were added to 2.5L of water in a bioreactor with an agitator to facilitate agitation. Baker’s yeast was added to enhance fermentation. The substrates were agitated for a total of 28.11 hours over 35 days. In the second batch, periodic manual agitation was employed. The pH and temperature were monitored, and gases produced were released occasionally.

- Sequence analysis, Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic analysis

The protein sequence of Cr(VI) reductase was obtained from UniProt and various physico-chemical properties were computed using ProtParam. Tools such as Virulentpred and VICM pred were used to study the virulence factor. Functions and families of the protein were predicted using tools hosted on InterProScan. Motifs were identified using InterProScan and Prosite tools.

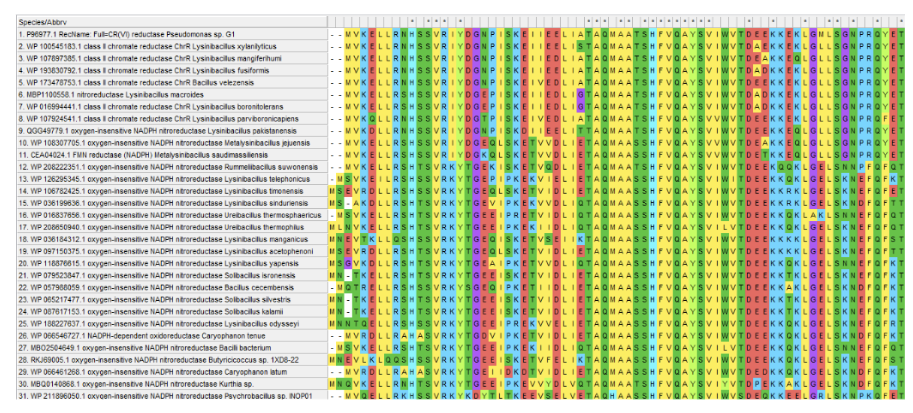

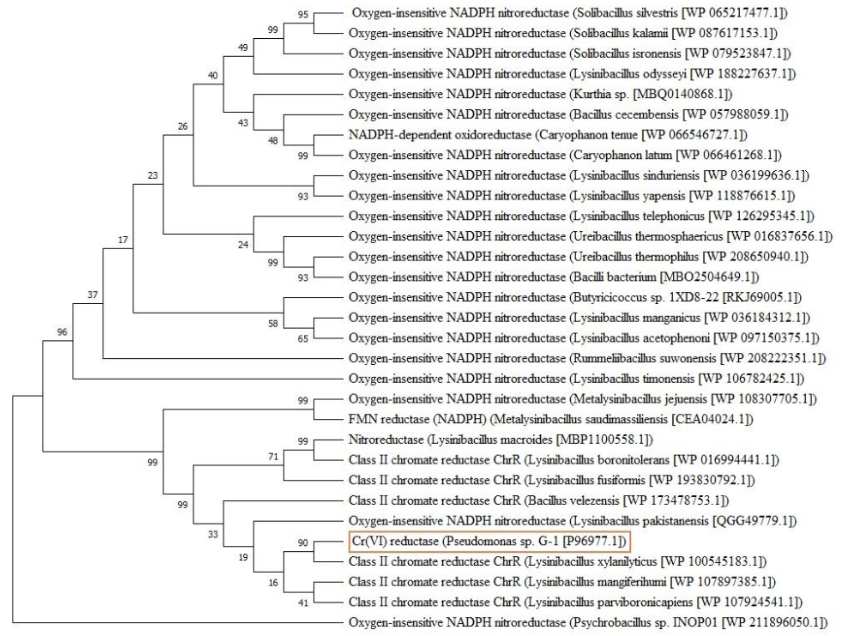

The protein sequence was analyzed to understand its homologous sequences, family, and domains. BLAST search was performed against non-redundant protein sequence databases, and sequences with query coverage greater than 50% and sequence similarity higher than 65% were included in the study. Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) was performed using the ClustalW tool to understand the relationship among sequences and recognize the conserved regions. The phylogenetic tree was built using the neighbor-joining algorithm and Poisson substitution method in MEGA-X software.

- Model Generation, Refinement, Validation

Ab Initio modelling was used to generate a 3D model of hexavalent chromium reductase. I-TASSER was used for model generation and the YASARA Energy Minimisation Server was used for refinement. The minimised structure was viewed on YASARA view and saved as a PDB file. After energy minimisation, the 3D model of hexavalent chromium reductase was validated using tools such as ERRAT, VERIFY3D, PROCHECK and ProSA available on the SAVES server. These tools check the stereochemical quality, residue-by-residue geometry and overall compatibility of the model with its amino acid sequence. The Z-score calculated by ProSA indicates the overall quality of the model and a plot of local quality scores can highlight problematic parts of the 3D model.

- Docking, Intramolecular Interaction Studies and Mutatgenesis

The model of hexavalent chromium reductase was generated using Ab Initio modelling and refined using YASARA Energy Minimisation Server. Model validation was performed using ERRAT, VERIFY3D, PROCHECK and ProSA. Docking studies were carried out using iGEMDOCK v2.1 with chromate and dichromate. In silico mutagenesis was used to predict the effects of single point mutations on the protein stability and select mutant residues with the highest and least DDG. Mutations were produced using Swiss-PDBViewer tool and the 3D models were generated using I-TASSER. Docking studies were performed for mutant models using iGEMDOCK.

Results and Discussion

- Results of bioenzyme, secondary structure prediction, model validation, docking and mutagenesis

The pH and temperature of bioenzyme fermentation in two bioreactors were measured and recorded. The pH decreased gradually during fermentation, indicating the production of ascorbic acid. The bioreactor with manual agitation had a slightly lower pH than the bioreactor with mechanical agitation. The temperature remained constant at around 30℃ in both reactors. After 35 days, the fermented product was filtered and centrifuged to obtain the purified bioenzyme. The concentration of ascorbic acid in the bioenzyme obtained from both the bioreactors was estimated by titrimetric analysis using iodine solution. The amount of ascorbic acid in the bioenzyme produced in the bioreactor with manual agitation and mechanical agitation was found to be 0.886 g L-1 and 0.871 g L-1 respectively.

The protein sequence of Cr(VI) reductase from Pseudomonas sp. (strain G-1) was obtained from UniProtKB with UniProt ID P96977. The enzyme has 243 amino acid residues and is encoded by the chrR gene. According to UniProtKB, it has oxidoreductase activity. Physico-chemical properties of the protein were calculated. The instability index indicates that the protein may be unstable, while the aliphatic index suggests that it may be thermostable. The GRAVY value is the sum of hydropathy values of all the amino acids, divided by the number of residues in the sequence.

MSA of chromium(VI) reductase homologs were obtained and aligned using the ClustalW tool. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbour-joining method with 30 orthologous sequences, which showed that the chromium(VI) reductase from Pseudomonas sp. G-1 strain was closely related to class II chromate reductase from Lysinibacillus xylanilyticus, Lysinibacillus mangiferihumi, and Lysinibacillus parviboronicapiens. The protein sequence also showed moderate homology to Metalysinibacillus saudimassiliensis and Metalysinibacillus jejuensis. The MSA and phylogenetic tree are shown below.

The sequence plot for the secondary structure prediction obtained illustrates annotated residues as per predicted secondary structures, including helices, strands, and coils. Additionally, the secondary structure prediction of chromium(VI) reductase on SOPMA indicated the presence of 54.32% alpha-helices, 4.12% beta-turns, and 28.4% random coils.

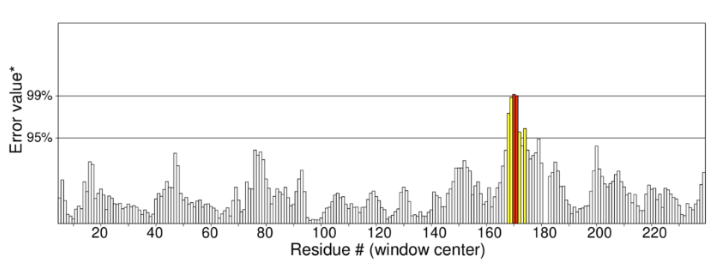

A 3D model of hexavalent chromium reductase was obtained from I-TASSER and energy-minimized on YASARA. The energy of the model before and after minimization was computed on Swiss-PDBViewer and observed to be -9474.395 kJ mol-1 and -10068.428 kJ mol-1, respectively. The final model was visualized on PyMOL. The energy minimized model of Cr(VI) reductase obtained from ERRAT had a good overall quality factor of 97.425%, indicating high quality. VERIFY3D analysis showed that 63.37% of the residues in the energy minimized 3D model had an average 3D-1D score of >=0.2, indicating that the model is suitable for further analysis.

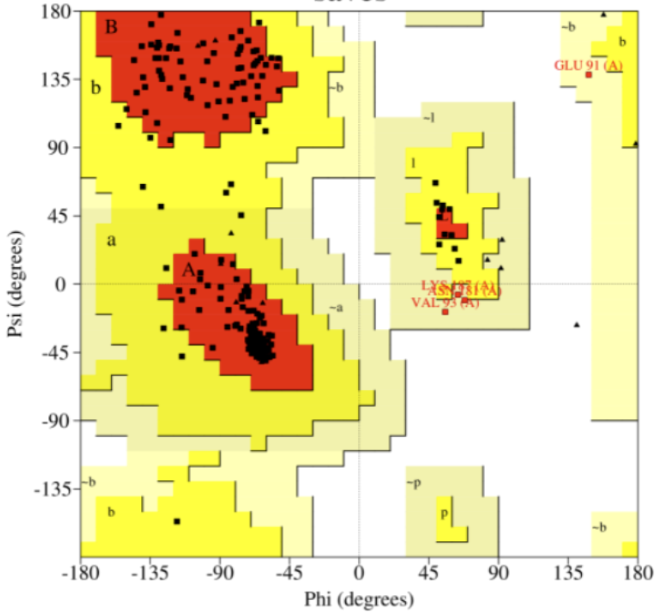

The 3D model of Cr(VI) reductase was stereo-chemically validated using the PROCHECK module of SAVES, and the Ramachandran plot indicated that 88.9% of the residues were in most favored regions, 9.3% in additional allowed regions, and 1.9% in generously allowed regions, with 0% in disallowed regions, confirming good model quality. The residue properties, maximum deviation, bad contacts, bond length/angle, and Morris et al class were also obtained. No bad contacts were found in the geometry of the protein model. The overall goodness of the model given by the G factor was 0.12, with dihedral and covalent G factor values of -0.08 and 0.40, respectively.

The ProSA web tool was used to evaluate the structural quality of Cr(VI) reductase, and the obtained ProSA Z-score of -7.08 indicated good model quality. Additionally, energies as a function of amino acid sequence position were plotted, and most residues fell within the negative energy minima region, indicating lower energy levels of the protein. Residue energies were also averaged over sliding windows of 10 and 40 residues and plotted as a function of the central residue in the window.

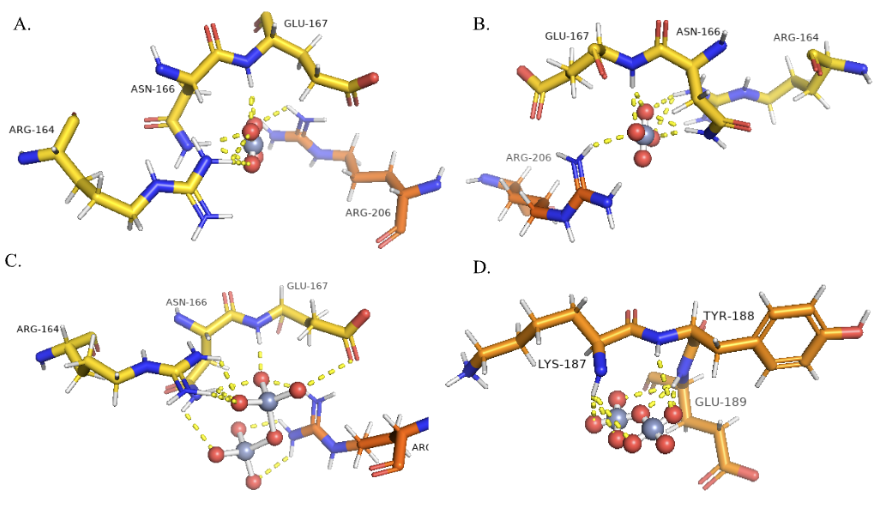

The docking results of hexavalent chromium reductase with chromate and dichromate were obtained from iGEMDOCK. The energy values for the docked complexes were tabulated in Table 5, where the total energy of Cr(VI)-dichromate complex was lower than that of Cr(VI)-chromate complex. The protein-ligand interactions were analysed and the residues involved in the interaction of Cr(VI) reductase with chromate were LYS 187, TYR 188, GLU 189 and GLU 186, while ARG 164, ASN 166, GLU 167 and ARG 206 were involved in the interaction with dichromate. The best docked poses of Cr(VI) reductase complex with chromate and dichromate were visualised on PyMOL.

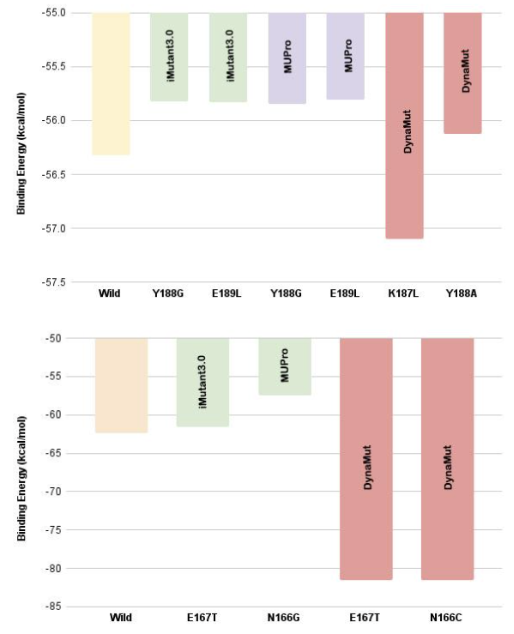

The study identified key residues involved in the interaction of Cr(VI) reductase with chromate and dichromate using I-Mutant, DynaMut, and MUPro tools. Mutations were carried out and 3D models were generated using I-TASSER, with the overall quality factor and 3D-1D scores indicating that the models are of adequate quality. iGEMDOCK was used for docking of the mutant models with chromate and dichromate, and it was observed that mutation of N166I resulted in a significant decrease in energy in the docked complex with dichromate.

Conclusion

The study focused on using bioenzyme produced from citrus fruit peels, jaggery, water and baker’s yeast for bioremediation of chromium in soil samples from agricultural fields. The study found that bioenzyme is a cost-effective and eco-friendly alternative to chemicals used in heavy metal degradation. The use of bioenzyme aids in better plant growth and productivity. The study also found that hexavalent chromium reductase found in chromium-resistant bacteria has the ability to catalyze the reduction of highly toxic Cr(VI) to less toxic Cr(III), offering a promising solution to chromium contamination. In silico site-directed mutagenesis indicated the importance of active site residues, which when mutated, brought about changes in the stability of the docked complex.